Java programming language

Object oriented programming

Class relatioships

Classes are not isolated elements in a program, usually. Objects of a class need to interact with objects of another class in many different ways, and that’s how relationship between classes are formalized. In this document we are going to see the main relationships that we can establish between classes: association, inheritance and dependency.

1. Class associations

Association is a relationship between two classes, in which one of them is part of the elements of the other one, this is, an object of one of the classes is an attribute or instance variable of the other class. It is usually represented in the code with a reference to the contained object or a collection or array of those objects. If we take back our example of a bookshop, we could say that a book has an author. Then, we can define a new class called Author with some attributes, such as the name and year of birth:

class Author

{

private String name;

private int yearBirth;

public Author(String name, int yearBirth)

{

this.name = name;

this.yearBirth = yearBirth;

}

public String getName()

{

return name;

}

public void setName(String name)

{

this.name = name;

}

public int getYearBirth() {

return yearBirth;

}

public void setYearBirth(int yearBirth) {

this.yearBirth = yearBirth;

}

}

We can establish a Has-A relationship between these two classes (a book has an author), so we define an association between them. To do this, our Book class will have an additional attribute to store the author of this book (we assume that every book has one, and only one, author). We need to add a new parameter to set the author from the constructor, and the corresponding getter and setter for this new attribute.

class Book

{

private String title;

private int numPages;

private double price;

private Author author;

public Book(String title, int numPages, double price, Author author)

{

this.title = title;

this.numPages = numPages;

this.price = price;

this.author = author;

}

...

public Author getAuthor()

{

return author;

}

public void setAuthor(Author author)

{

this.author = author;

}

}

Regarding our main program, we can define an Author object and associate it to a given book. Then, we can print the typical information of the book… but also author’s information, such as author’s name:

public class BookExample

{

public static void main(String[] args)

{

Author a = new Author("J.R.R. Tolkien", 1892);

// The lord of the Rings, 850 pages, 13.50 eur, Tolkien

Book b = new Book("The lord of the Rings", 850, 13.50, a);

// Print book title and author's name

System.out.println(b.getTitle());

System.out.println(b.getAuthor().getName());

}

}

Note that, if we want to associate the same author to more than one book, we just need to use the same object, instead of creating/repeating the object again for every new book.

Author a1 = new Author("J.R.R. Tolkien", 1892);

Author a2 = new Author("J.R.R. Tolkien", 1892);

// a2 is not the same than a1 (different objects in memory)

Book b1 = new Book("The lord of the Rings", 850, 13.50, a1);

Book b2 = new Book("The hobbit", 345, 8.76, a2); // Different author

Book b3 = new Book("The hobbit", 345, 8.76, a1); // Same author

Exercise 1:

Improve exercise TeamsExample.java from previous document in another source file called TeamsExample2.java. Now every team will have an array of 5 players. Add a new class called

Playerto the source file. For each player, we need to define his/her name, age and back number. Add the corresponding constructor and getters/setters. Then, modifyTeamclass to store 5 Player objects, and adapt your main function to create a team with all the players inside it. Print the information of the team, including the players that belong to it.

Exercise 2:

Improve exercise VideoGameList.java from previous document in another source file called VideoGameList2.java. Now, every video game has a Company that created it. For every company, we need to store its name and the foundation year. Associate a company to each video game, so that some video games can share the same company object. Then, modify the main application to specify the company information for every videogame (besides video game initial data). Make sure that you share the same Company object among all the video games belonging to the same company.

1.1. Association navigability

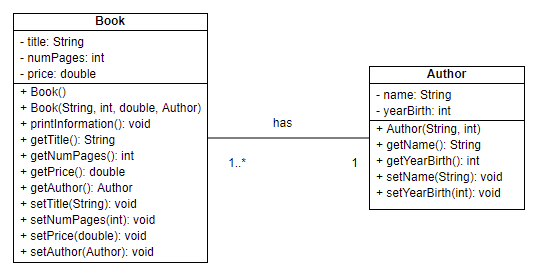

Associations are (or can be) bi-directional. In a class diagram, they are represented by a continuous line joining both clases involved, including the cardinality of each one in the relationship. In our case, a Book has one author, and an author can have many books. This can be represented like this:

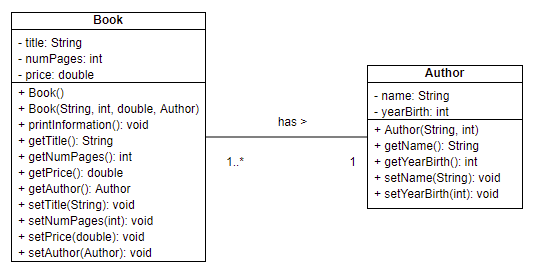

However, if we don’t specify it, associations are (by default) bi-directional. This means that we can retrieve the author of a book from the book object (we can do this, already), but we can also retrieve the list of books of an author from the author object. This last part of the relationship is not implemented in our example, so, unless we want to implement it, we need to represent this association as unidirectional, by adding an arrow pointing to Author class. This means that we can get the author from a book object, but not the opposite. The arrow can be placed at either the line or the association name.

The programmer can decide if an association needs to be bi-directional or not, so only one of the classes (or both) will be related with the other one.

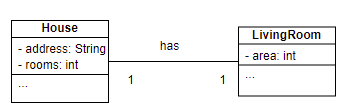

Let’s have a look at this example: we have a House class to represent houses. From each class, we want to know the address, and the total number of rooms. Each house has a living room, so we use a LivingRoom class to represent it. We store the total area of the living room. We can establish a one-to-one relationship between these classes (a house has one living room, and a living room belongs to one house):

Now, we are going to represent this bi-directional relationship in Java. First of all, we add a LivingRoom object as attribute in House class, and we assign it in the constructor:

class House

{

private String address;

private int rooms;

private LivingRoom livingRoom;

public House(String address, int rooms, LivingRoom livingRoom)

{

this.address = address;

this.rooms = rooms;

this.livingRoom = livingRoom;

}

public String getAddress()

{

return address;

}

public void setAddress(String address)

{

this.address = address;

}

public int getRooms()

{

return rooms;

}

public void setRooms(int rooms)

{

this.rooms = rooms;

}

public LivingRoom getLivingRoom()

{

return livingRoom;

}

public void setLivingRoom(LivingRoom livingRoom)

{

this.livingRoom = livingRoom;

}

}

Next, we try to do the same with LivingRoom class (we add a House object and try to assign it in the constructor):

class LivingRoom

{

private int area;

private House house;

public LivingRoom(int area, House house)

{

this.area = area;

this.house = house;

}

public int getArea()

{

return area;

}

public void setArea(int area)

{

this.area = area;

}

public House getHouse()

{

return house;

}

public void setHouse(House house)

{

this.house = house;

}

}

But let’s try to create both objects from a main program:

LivingRoom lr = new LivingRoom(40, ???); // Where's the house??

House h = new House("Java Street", 3, lr); // LivingRoom is OK

As you can see, one of the constructors is missing some information. When we want to establish a bi-directional association between two classes, one of them can be set in the constructor, but the other one (the first object that we create) must wait. So the constructor of LivingRoom class does not need a House parameter:

public LivingRoom(int area)

{

this.area = area;

// House remains unassigned

}

Then, we have two options to assign the house to a living room:

- We call the setter from

LivingRoomonce the house has been created:

LivingRoom lr = new LivingRoom(40);

House h = new House("Java Street", 3, lr);

lr.setHouse(h);

- We can do this automatically in the house constructor, as soon as we assign the living room to it:

public House(String address, int rooms, LivingRoom livingRoom)

{

this.address = address;

this.rooms = rooms;

this.livingRoom = livingRoom;

// Assign the livingRoom to this house

this.livingRoom.setHouse(this);

}

If we use this last way, we don’t need any additional outer code. As soon as we instantiate both objects, they are automatically associated:

LivingRoom lr = new LivingRoom(40);

House h = new House("Java Street", 3, lr);

// At this point, association is already bi-directional

Exercise 3:

Create a source file called BookAssociation.java. Add the

BookandAuthorclass that we have already implemented in previous example, and try to make this association bi-directional. In this case, you need to add aBookarray as an attribute inAuthorclass, and add the corresponding code to add books to each author’s array.

1.2. Aggregations and compositions

There are two special types of associations: compositions and aggregations. In both, one of the classes is considered as a whole thing, and the other one is a part of this whole thing. But… how to distinguish between composition and aggregation? Let’s see it with some simple examples:

- Composition: we use it when an object is an indivisible part of another object. For example, a

Roomis part of aHouse(and only of that house), aSquareis part of aChessboard, and so on. The main characteristic of this type of relationship is that when we destroy the main object (the whole thing), all objects that are part of it are also destroyed. - Aggregation: we use it when an object is part of another object (or maybe part of two or more objects) and it can exist without the object that contains it. An example of this would be a

Player, who is part of aTeam(or maybe more), or aStudent, who belongs to aClassrom(or more). In these cases when theTeamor theClassroomno longer exists, players and students continue to exist, and they can join other team/classroom.

Composition and aggregation in practice

In practice, the way we define the aggregation or composition depends on the programming language that we are using. But, in general, if the internal attribute or instance variable that makes the composition or aggregation can’t be accessed from out of the containing class, then we have a composition. Otherwise, we have an aggregation. Let’s see this with the following example: we define a Car class that has an object of type Engine. If we want to define a composition between these classes, we would do it this way:

class Car

{

private final Engine engine;

public Car(EngineParams params)

{

engine = new Engine(params);

}

}

Note that we create the Engine object inside the Car class, by using some parameters specified in the EngineParams object. This object may contain some simple data about the engine, such as power, or fuel consumption. In this case, if the Car object is destroyed, then the Engine object will be destroyed as well. There’s no way to access the engine beyond this class. So, this is a composition.

However, if we need to define an aggregation between Car class and Engine class, then we do it like this:

class Car

{

private Engine engine;

public Car(Engine engine)

{

this.engine = engine;

}

public Engine getEngine()

{

return engine;

}

...

}

In this case, we are using an external object of type Engine to create the internal Engine object of the car (we pass this external object as a parameter to the constructor), so the engine can exist without the car: if we destroy the car, the external engine that we used in the constructor will keep on existing. This can be useful if we want to use the engine in another car, once the old one is destroyed.

Note that aggregations and simple associations are implemented in the same way in Java programs. Compositions are more tricky and, unless we have a good reason to implement them, they can also act as aggregations.

2. Class inheritance

We use inheritance when we want to create a new class that takes all the features of another one, adding its particular ones. For instance, if we have an Animal class with a set of attributes (name, weight…) and methods, we can inherit from it to create a new class called Dog that will also have all these features, and we can add some additional ones, such as a bark() method.

We have seen in previous sections of this document how to identify an association, by finding a Has-A relationship between the classes involved. When talking about inheritance, we identify it with an Is-A relationship, so that one class is a subtype of another class. In other words, it shares the features of the ancestor and introduces some new ones. One example of this is a Car, which is a subtype of Vehicle. Another could be a ComputerClassroom, which is a subtype of Classroom that also has computers in it.

When we want a class to inherit the features from another class in Java we use the reserved word extends in the new class (also called child class or subclass), referring to the class from which we want to extend (also called parent class or superclass).

class Dog extends Animal

{

...

}

class Car extends Vehicle

{

...

}

Let’s go back to our bookshop example. What if we want to add information for a specific type of book, such as comics? We can add, for instance, if they are in color or not (grayscale), and also the volume number for a comic series. We could create a brand new class with all the information, like this one:

class Comic

{

private String title;

private int numPages;

private double price;

private boolean color;

private int volumeNumber;

// Constructors, getters, setters and so on...

}

But, as a comic is a subtype of book, we can inherit from Book class and automatically include all the elements of this class (this is, the title, number of pages, price, getters, setters…). Then, we only need to care about the new, specific information for comic elements:

class Comic extends Book

{

private boolean color;

private int volumeNumber;

public Comic(String title, int numPages, double price,

boolean color, int volumeNumber)

{

this.title = title;

this.numPages = numPages;

this.price = price;

this.color = color;

this.volumeNumber = volumeNumber;

}

public boolean getColor()

{

return color;

}

public void setColor(boolean color)

{

this.color = color;

}

public int getVolumeNumber()

{

return volumeNumber;

}

public void setVolumeNumber(int volumeNumber)

{

this.volumeNumber = volumeNumber;

}

}

2.1. Visibility and inheritance

Note that, in the constructor, we need to specify EVERY attribute for the object that we are creating. As comic extends book functionality, we need to provide the title, number of pages and price, along with the color and volume number. However, there’s a problem if we try to compile and run previous code: title, number of pages and price are private members of Book class, so they can’t be accessed from outer classes. We should not declare them public, since it’s not recommended. Fortunately, there’s an additional, intermediate access level that we can use, which is protected.

We use the protected access modifier to let child classes access parent information. It’s generally used in attributes of a parent class, such as our Book class. We change the visibility this way:

class Book

{

protected String title;

protected int numPages;

protected double price;

// The rest of code does not change

}

So, to sum up, now that we have learnt what inheritance means, there are four different visibility levels in Java. Here you can see them from higher to lower:

- public elements can be accessed from any other part of the code (including other classes and packages)

- protected elements can only be accessed from any subclass of current class, or any class from the same package than current class

- package (default): elements are only accessible from the same package.

- private elements can only be accessed from current class

Let’s see all these modifiers in an example:

public class MyClass

{

// Accessible everywhere

public int number;

// Accessible from subclasses or same package

protected String name;

// Only accessible from this class

private float average;

// Package level, accessible from same package

char symbol;

2.2. Overriding parent’s behavior. Using super

When we define a class that is a subtype of another class using inheritance, we can modify or override the behavior of parent methods in child class. For instance, printInformation method in Book class just prints the basic information (title, pages and price):

public void printInformation()

{

System.out.println("Book information:");

System.out.println("Title: " + title);

System.out.println("Pages: " + numPages);

System.out.println("Price: " + price);

}

But, in this new class, we need to add specific information about the comic. So we can write again this method in Comic class, and add an annotation called @Override to specify that this method belongs to parent class, but we are changing its behavior in child class:

class Comic extends Book

{

...

@Override

public void printInformation()

{

System.out.println("Book information:");

System.out.println("Title: " + title);

System.out.println("Pages: " + numPages);

System.out.println("Price: " + price);

System.out.println("Color/Grayscale: " +

(color?"Color":"Grayscale"));

System.out.println("Volume: " + volumeNumber);

}

}

Moreover, we can make use of a specific reserved word called super to get to a parent’s element. In this case, we are repeating the same code of parent’s printInformation method, so we can just call this parent’s method using super:

class Comic extends Book

{

...

@Override

public void printInformation()

{

super.printInformation();

System.out.println("Color/Grayscale: " +

(color?"Color":"Grayscale"));

System.out.println("Volume: " + volumeNumber);

}

}

NOTE:

@Overrideannotation is NOT compulsory for the program to compile, but you should use it in terms of code cleanliness, since you are specifying that this method does not belong to current class, it’s just another version of an existing method in parent class.

Constructors and inheritance

Let’s take a look again at Comic constructor in previous example:

public Comic(String title, int numPages, double price,

boolean color, int volumeNumber)

{

this.title = title;

this.numPages = numPages;

this.price = price;

this.color = color;

this.volumeNumber = volumeNumber;

}

Whenever we call a constructor from a subclass, the default constructor (i.e. the one with no parameters) of the superclass is automatically called (unless we use super to choose another constructor). So the code above will work as long as Book has a default constructor. Otherwise, we should:

- Define a default (even empty) constructor in

Bookclass - Choose with

superanother different parent constructor fromComicclass. In this case, we can make use of the parameterized constructor ofBookclass and avoid assigning book’s attributes from child class:

public Comic(String title, int numPages, double price,

boolean color, int volumeNumber)

{

super(title, numPages, price);

this.color = color;

this.volumeNumber = volumeNumber;

}

NOTE: if you use

superinstruction in a child constructor to invoke a specific constructor from parent class, this instruction MUST be the first in child constructor.

2.3. Extending Object class

We must take into account that, unless we specify another inheritance, every class in Java inherits from a global, parent class called Object. So, if our class does not inherit from any other class, it will automatically be a child of Object class, and thus, it can use or override methods from this class, such as equals or toString.

If we override toString method, we can then convert our objects to strings, and then print them easily. Let’s suppose that we override this method in a Person class, so that we return a string with the person’s name and age between parentheses:

public class Person

{

private String name;

private int age;

public Person(String n, int a)

{

name = n;

age = a;

}

@Override

public String toString()

{

return name + " (" + age + " years)";

}

}

Then, we can easily print any Person object by simply calling System.out.println sentence:

Person p = new Person("Nacho", 40);

System.out.println(p); // Prints "Nacho (40 years)"

In the same way, we can also override equals method to determine if two Person objects are equal or not. In this example, we say that they are equal if they have the same name and age:

public class Person

{

private String name;

private int age;

public Person(String n, int a)

{

name = n;

age = a;

}

@Override

public String toString()

{

return name + " (" + age + " years)";

}

@Override

public boolean equals(Object p)

{

Person p2 = (Person) p;

return this.name.equals(p.name) && this.age == p.age;

}

}

Then, we can compare two Person objects and determine if they are equal or not:

Person p1 = new Person("Nacho", 40);

Person p2 = new Person("Nacho", 39);

if (p1.equals(p2))

{

System.out.println("They are equal!");

} else {

System.out.println("They are different");

}

2.4. Polymorphism

The term polymorphism refers to the ability of an element to have multiple shapes or appearances. For instance, a class can have many methods with the same name and different number or types of parameters. This is a kind of polymorphism which is also called method overload. We can call any of these method versions depending on our needs.

Regarding object oriented programming, polymorphism is the ability of an object to behave like another object. This term is commonly used in inheritance to show that an object of any class can behave like any of its subclasses. For instance, a Vehicle object of previous examples could behave like a Car object, so we can, for instance:

- Instantiate a

Carobject from aVehiclevariable:

Vehicle myCar = new Car(...);

- Use a

Carobject as a parameter to a method which gets aVehicleobject.

public void aMethod(Vehicle v)

{

...

}

...

Car anotherCar = new Car(...);

aMethod(anotherCar);

- Fill an array of

Vehicleobjects with any subtype ofVehiclein each position:

Vehicle[] vehicles = new Vehicle[10];

vehicles[0] = new Vehicle(...);

vehicles[1] = new Car(...);

vehicles[2] = new Van(...);

...

However, we must take into account that, when using polymorphism, the polymorphic variable can only access the methods of the type to which it belongs. In other words, if we create a Car object and store it in a Vehicle variable, then we will only be able to call methods or public elements from Vehicle class (not from Car class).

Vehicle myCar = new Car(...);

myCar.vehicleData(); // OK

System.out.println(myCar.getNumberOfDoors()); // ERROR

If we want to detect the concrete type of an object in order to access its own methods (and not only those inherited from parent class), then we can use instanceof operator, and then make a typecast to the concrete type:

Vehicle[] vehicles = new Vehicle[10];

... // Fill the array with many vehicle types

for (int i = 0; i < vehicles.length; i++)

{

if (vehicles[i] instanceof Car)

{

System.out.println(((Car)vehicles[i]).getNumberOfDoors());

} else if (vehicles[i] instanceof Van) {

...

} ...

}

Exercise 4:

Improve previous exercise TeamsExample2.java in another source file called TeamsExample3.java. Add a new class called

Captainwhich inherits fromPlayerclass. It will have an additional attribute specifying the years of experience of the captain. Define the corresponding constructor (usingsuperto fill parent’s data) and modify the main function to include a Captain object in the team.

Exercise 5:

Improve previous exercise VideoGameList2.java in another source file called VideoGameList3.java. Add a new class called

PCVideoGamewhich inherits fromVideoGameclass. It will have two new attributes called minimumRAM and minimumHD to store the minimum amount of RAM memory and hard disk space required to play the game (both integers). Define the corresponding constructor to set these values (and usesuperto call parent’s constructor to set the inherited values). Then, add some PC video games to the array and repeat the same steps than in previous exercise.Also override

toStringmethod in VideoGame class so that we can print a video game in the screen with its information by symply callingSystem.out.println.

2.5. Exceptions and inheritance

We can create our own exceptions by creating classes that inherit from Exception class. We can then throw a custom exception whenever we want and manage it in the method that throws it or send it up to the method it will return to.

public class CustomException extends Exception

{

public CustomException(String msg)

{

super(msg);

}

}

public class Store

{

public void welcome() throws CustomException

{

throw new CustomException("Error, nobody can pass!");

}

}

public static void main(String[] args)

{

Store store = new Store();

try

{

// This method can throw a CustomException

store.welcome();

} catch (CustomException e) {

System.err.println(e.getMessage());

}

}

Exercise 6:

Create a new source file called CustomException.java. In this source file you’re going to implement:

- A class called

NegativeSubtractException. This class will inherit fromExceptionand will be created when a subtraction result is negative. The constructor will receive 2 parameters (the two numbers that caused a negative subtraction result in order). The message generated will be: “NegativeSubstractException: ‘N1 - N2’ result is negative”.- In the main class create a static function that throws this type of custom exception. This method will be called

static int positiveSubtract(int n1, int n2), and will generate and throw this kind of exception if the result is negative. Within the main method call this method with parameters that would give a negative result and catch the corresponding exception, showing its message on console.

3. Class dependency

Dependency relationship establishes a connection between two classes when one of them uses an object of the other one in some part of its code, BUT there’s no association between them (this is, there’s no attribute of one class in the other class).

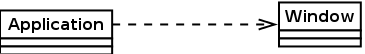

If we take a look at this example, there’s a dependency between Application and Window class. This can be due to a method in Application class that receives a Window parameter, for instance. But there’s no Window attribute in Application class:

class Application

{

...

public void aMethod(Window w)

{

...

}

}

Also, there could be a piece of code inside a method that instantiates a Window object. In this case, there would also be a dependency relationship between these classes:

class Application

{

...

public void aMethod()

{

Window w = new Window(...);

...

}

}