Java programming language

Object oriented programming

Classes and objects in Java

When we talk about Object Oriented Programming (OOP), we are talking about a new approach to face software projects, in which we don’t focus on what the program must do, but in which elements are part of the system, and how they interact. These elements are categorized in classes, and from each class we create objects in the program. In this document we will explain what a class is, and how to define them in Java to create objects.

1. Classes and objects

Let’s suppose that we are going to implement an application for bookshop management. In this library there are many books, and each one has an author, and some basic information about the book (title, number of pages, price…). The library has many registered users or customers that want to buy some books.

If we start thinking how to implement this application with the elements that we have learnt so far, we would define some variables to store the information: maybe a string array to store book titles, another string array to store customer names… and so on. And then, we would define the functions to search for a book in the array, to look for user data to login…

Object oriented programming changes the starting point of view of this project. Instead of thinking about functionality (book search, user login…) we just think about the different elements that will be part of the project. In this case, our application will have books, authors, customers… these elements will be the classes of our project. In other words, classes are templates that categorize the different elements of the application.

For each class, we need to store some useful information. For instance, for every book we need to know the title, number of pages and price. This information are the attributes of each class. Once we know the attributes of a class, we can create objects of this class. An object is a concrete instance or representation of a class. We could create a book with a concrete title (e.g. “Ender’s game”), a concrete number of pages (e.g. 321), and so on. And there can be many objects of a class when our application is running (in our case, we could have many books created in our bookshop). In the same way, we could define the attributes of the rest of classes (customers, authors…) and instantiate objects of each class.

Every object in the application may need to do some operations. For instance, we may need to print the information of a book in the screen, and customers may need to search for books, or buy them. These operations are called methods of this class.

So with object oriented programming we need to identify these elements of the application, and define the classes to represent them. Later, we will be able to create or instantiate objects of each class. Let’s see how to do this in Java.

2. Defining classes in Java

As you have seen before, every piece of code in Java is encapsulated in a class. We define classes in Java through the class word, asigning each class a name (usually in upper case). We usually place every class in its own source file, and this class must be public.

Inside the class code, we can place the attributes of the class, also called instance variables. These variables are part of the class. For instance, this way we could define a Book class for our bookshop, with its own attributes:

class Book

{

String title;

int numPages;

double price;

}

2.1. Creating objects

Once we have defined our class(es), we can create objects of them. In order to do this, we need to declare a variable of the same type of the class, and use the new operator to create the object:

Book myBook = new Book();

At this point, myBook becomes an object of class Book, and it contains every attribute defined in this class. We can access each attribute using the . operator, and then check or modify its value:

Book myBook = new Book();

myBook.title = "Ender's game";

myBook.numPages = 321;

myBook.price = 11.95;

We can place this code in another class and do some more things with this object:

class BookExample

{

public static void main(String[] args)

{

Book myBook = new Book();

myBook.title = "Ender's game";

myBook.numPages = 321;

myBook.price = 11.95;

System.out.println("Book information:");

System.out.println("Title: " + myBook.title);

System.out.println("Pages: " + myBook.numPages);

System.out.println("Price: " + myBook.price);

}

}

NOTE:

mainmethod is usually defined in another class apart from the elements of the program. It makes sense, since this method does not belong to any of these classes.

NOTE: in Java, every source file must have a public class with the same name than the source file. In other words, if we create a source file called

MyClass.java, there must be a public class calledMyClassin this source file. There can be also other (non public) classes there, although this is not usual, unless we just want one source file in our project. In this case, the class with the main function must be the public class in the file.

3. Defining more class elements

3.1. Using methods

If we think a little bit about previous example, what if we want to print the information of many books? We could either:

- Repeat the

System.out.printlninstructions for every book - Define a function in

BookExampleclass to be called whenever we want to print the information of a book. In this case, we should pass the book as a parameter to this function in order to print the information.

But there’s one more option that we have not used by now. What if every book is in charge of printing its own information? This way, we could define a function inside Book class, and access directly to the information of each book:

class Book

{

String title;

int numPages;

double price;

void printInformation()

{

System.out.println("Book information:");

System.out.println("Title: " + title);

System.out.println("Pages: " + numPages);

System.out.println("Price: " + price);

}

}

Now, our main class just needs to call this function (which is a method of Book class) to invoke this behavior:

class BookExample

{

public static void main(String[] args)

{

Book myBook = new Book();

myBook.title = "Ender's game";

myBook.numPages = 321;

myBook.price = 11.95;

myBook.printInformation();

Book myBook2 = new Book();

myBook2.title = "The never ending story";

myBook2.numPages = 525;

myBook2.price = 14.15;

myBook2.printInformation();

}

}

Note that methods are just functions belonging to a class. In this case, we don’t need to use the static modifier (we will see in later documents what static really means). This is an instance method, this is, every object or instance of the class has its own method and this method access current object’s information.

3.2. Constructors

Let’s go back to previous example. What if our book had 10 o 20 attributes? Do we have to manually set every attribute every time we instantiate an object? Fortunately, the answer to this question is NO. We can use constructors to initialize the objects when we create them. They have the same name than the class to which they belong, and they are defined like a method, but they don’t have any return type.

Inside the code of a constructor, we typically assign initial values to instance variables or attributes, and call any other method that may be useful at the beginning of the object’s lifetime.

Let’s go on with our Book class. In this case, we are going to add a constructor with no parameters, also known as default constructor. We will use it whenever we need to create an object of this class.

class Book

{

String title;

int numPages;

double price;

// Default constructor

Book()

{

title = "";

numPages = 0;

price = 0;

}

void printInformation()

{

System.out.println("Book information:");

System.out.println("Title: " + title);

System.out.println("Pages: " + numPages);

System.out.println("Price: " + price);

}

}

class BookExample

{

public static void main(String[] args)

{

Book myBook = new Book();

myBook.printInformation();

Book myBook2 = new Book();

myBook2.printInformation();

}

}

The output that we would get in this case is different, since we have not set the instance variables manually, but through the default constructor, so all of them are empty strings or 0.

In some cases, we may need to assign some non-default values to the instance variables, so we use a constructor with parameters. Typically, each parameter corresponds to an instance variable or attribute.

class Book

{

String title;

int numPages;

double price;

// Default constructor

Book()

{

title = "";

numPages = 0;

price = 0;

}

// Parameterized constructor

Book(String t, int n, float p)

{

title = t;

numPages = n;

price = p;

}

void printInformation()

{

System.out.println("Book information:");

System.out.println("Title: " + title);

System.out.println("Pages: " + numPages);

System.out.println("Price: " + price);

}

}

Using this constructor, we would create a Book object as follows:

Book myBook = new Book("Ender's game", 321, 11.95);

We can have as many constructors as we need. All of them will have the same name (the class name), but they will have different parameters.

3.3. Visibility and encapsulation

Visibility is something essential in object oriented programming. It establishes which elements are visible from which other classes of our code. This is managed through access modifiers, special words that we can place before any attribute or method of our class (including constructors) to determine their visibility. To begin with, there are two main types of visibility:

- public: we will be able to access this member directly from any part of the code, including any other class.

- private modifier, we would only be able to access this member from other members of the same class. Out of this class, this member is not visible.

Additionally, there are two more modifiers that we can use in Java applications:

- protected: we will use this modifier later, when we talk about inheritance.

- package: this is the default modifier if we don’t use any. It means that every class from the same package can access this element. If we place many classes in the same source file, they belong to the same package, so we can access any package element of any of these classes.

In general, class attributes should be defined as private, so that they can’t be modified accidentally from other classes. However, class methods are usually public, so they can be called from any other class. Our Book class should be defined like this:

class Book

{

private String title;

private int numPages;

private double price;

// Default constructor

public Book()

{

title = "";

numPages = 0;

price = 0;

}

// Parameterized constructor

public Book(String t, int n, float p)

{

title = t;

numPages = n;

price = p;

}

public void printInformation()

{

System.out.println("Book information:");

System.out.println("Title: " + title);

System.out.println("Pages: " + numPages);

System.out.println("Price: " + price);

}

}

Now, lets try to modify our main function. If we try to do something like this now, we will get a compilation error:

class BookExample

{

public static void main(String[] args)

{

Book myBook = new Book("Ender's game", 321, 11.95);

System.out.println("This book is " + myBook.title);

}

}

The problem is that title attribute is private, so we can’t access it from BookExample class. We need a way to access object’s information from outer classes.

3.3.1. Getters and setters

There’s a specific set of methods that we can implement to access information. These methods are called getters and setters and we can use them to either get or modify each attribute. In general, getters are defined with get prefix followed by the attribute name to which they refer. These would be the getters for our Book class:

class Book

{

private String title;

private int numPages;

private double price;

// Default constructor

public Book()

{

title = "";

numPages = 0;

price = 0;

}

// Parameterized constructor

public Book(String t, int n, float p)

{

title = t;

numPages = n;

price = p;

}

public void printInformation()

{

System.out.println("Book information:");

System.out.println("Title: " + title);

System.out.println("Pages: " + numPages);

System.out.println("Price: " + price);

}

// Getters

public String getTitle()

{

return title;

}

public int getNumPages()

{

return numPages;

}

public double getPrice()

{

return price;

}

}

As you can see, each getter method just returns the associated attribute. We can use them in previous example to access book information:

class BookExample

{

public static void main(String[] args)

{

Book myBook = new Book("Ender's game", 321, 11.95);

System.out.println("This book is " + myBook.getTitle());

}

}

In the same way, setters let us modify the values of the attributes in a safe way. What if we try to assign a negative number of pages? Setter method can take care of this, and make sure that the value we are assigning is correct:

class Book

{

private String title;

private int numPages;

private double price;

// Default constructor

public Book()

{

title = "";

numPages = 0;

price = 0;

}

// Parameterized constructor

public Book(String t, int n, float p)

{

title = t;

numPages = n;

price = p;

}

public void printInformation()

{

System.out.println("Book information:");

System.out.println("Title: " + title);

System.out.println("Pages: " + numPages);

System.out.println("Price: " + price);

}

// Getters

public String getTitle()

{

return title;

}

public int getNumPages()

{

return numPages;

}

public double getPrice()

{

return price;

}

// Setters

public void setTitle(String t)

{

title = t;

}

public void setNumPages(int n)

{

if (n > 0)

numPages = n;

}

public void setPrice(double p)

{

if (p >= 0)

price = p;

}

}

Note that, for numPages and price attributes, we check if new value to be assigned (which is passed as a parameter to the method) is correct. This way, we protect the attribute from wrong values. This is called encapsulation (hide private attribute and only allow the access through getters and setters). We can even use these setters from the constructors, to make sure we also assign correct values there:

public Book(String t, int n, float p)

{

title = t;

setNumPages(n);

setPrice(p);

}

Exercise 1:

Create a source file called TeamsExample.java. Define a class called

Teamwith some specific information about the teams, such as the team name and the foundation year. Add a constructor to this class to specify both attributes, and the corresponding getters and setters. Then, define a main class calledTeamsExamplewith a main function that creates a Team object with the values of your choice, and prints the information in the screen.

4. Other aspects regarding classes and objects

To finish with this introduction to class management in Java, let’s check some additional concepts related with class definition and object instantiation.

4.1. More about constructors and attributes

If we don’t define any constructor in our class, Java automatically adds a default constructor (with no code nor parameters), so that we can instantiate objects of our class anyway. For instance, if we have this simple class:

public class Person

{

String name;

int age;

}

We can create a Person object like this, even if we have not specified such constructor:

Person p = new Person();

However, if we set any constructor in our class, then this default constructor that has been automatically added is no longer available. In other words, if we add this constructor to previous class:

public class Person

{

String name;

int age;

public Person(String n, int a)

{

name = n;

age = a;

}

}

Then we are forced to instantiate objects of our class with this constructor (or any other constructor that we have explicitly declared):

Person p = new Person("Nacho", 40); // OK

Person p2 = new Person(); // ERROR!

4.1.1. Default values for attributes

If we don’t assign any value to a class attribute, it gets a default value depending on the data type. For numeric values (integers or real numbers), this value is 0. Regarding characters, this value is the first character code '\u0000'. Strings get null as its default value, and boolean variables are false by default.

However, it is not a good practice to rely on these default values in our programs. It is better to assign an initial value to our variables instead.

NOTE: these default values are NOT applied to local variables. In other words, if we declare an integer variable inside a function or method, it will not be assigned a default value, and we will get a compilation error if we don’t assign it an appropriate one. But, if we declare an array of integer values, they will all be set to 0 initially, even if the array is local to a method.

4.2. Using this

In every class that we are implementing, we can use the reserved word this to refer to any internal element of the class, either an attribute, a method or a constructor. Its main typical use relies on constructors, to distinguish between the attributes and the constructor parameter(s) when they have the same name:

class Book

{

private String title;

private int numPages;

private double price;

public Book(String title, int numPages, float price)

{

this.title = title;

this.numPages = numPages;

this.price = price;

}

But we can also use this in any other part of our code:

class Book

{

...

public void setPrice(double price)

{

if (price >= 0)

this.price = price;

}

}

Keep in mind that the usage of this is (usually) optional, but many IDEs generate code templates using this pattern, so you should get used to it.

4.3. Arrays of objects

We can define an array of objects of a class, like we did with primitive data in previous sections. For instance, this is how we would create an array to store up to 10 books:

Book[] books = new Book[10];

However, we need to instantiate (create) a new object for every position of the array in order to add it to this position:

books[0] = new Book("Ender's game", 321, 11.95);

books[1] = new Book("The never ending story", 525, 14.15);

...

// Or with a loop:

for (int i = 0; i < books.length; i++)

{

books[i] = new Book(...);

}

Exercise 2:

Create a program called VideoGameList.java to store objects of a class called

VideoGamethat you must define. For each videogame, we are going to store its title, genre and price. Add also the corresponding getters, setters and constructor to set these values. Define a main, public class calledVideoGameListin the same source file. Then, in the main method of this class, create an array of 5 video games, ask the user to fill de information of each videogame, and then show the title of the cheapest and the most expensive video game of the array.

5. Class diagrams in Java

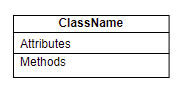

Class diagrams are a powerful tool in software engineering in order to graphically represent the classes of a project and their relationships. You can learn more about class diagrams here. As you can see, classes in these diagrams are represented by a box divided in 3 sections: one to specify the class name, another one for the attributes, and the last one for the methods (including constructors):

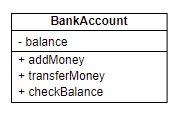

In order to specify each attribute or method, we can set its visibility using the + and - symbols (representing public and private visibility, respectively). This is how we could represent a BankAccount class with basic information and methods:

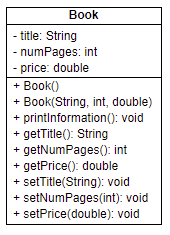

Regarding Java, we also need to specify the data type of each attribute, along with the type of every method (including parameters and return type). This is an example of our Book class represented in a class diagram:

Exercise 3:

Complete the class diagrams proposed along this document, including Java data types for every attribute, constructor or method.